In the distant past of Precambrian times, the Mojave Desert

region was covered in shallow water (Webb 21). Tectonic activities and crust

formation shaped the alternating mountain ranges and valleys that make up the

region today, and as the water gradually receded, the landscape slowly emerged

onto the surface during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Era, washed-up sediments

formed thick limestone and dolomite deposits (Webb 59-69). When the first

humans arrived nearly 15,500 years ago, the Mojave Desert had a moist and cool

climate, with streams, marshes, and plentiful large game (mojavedesert.net).

The natives quickly took advantage of this environment and began their

adjustment to the region, forming the tribal Indian groups discovered by the

first Spanish explorers much later on, in 1776 (mojavedesert.net). As in

all instances of contact between Native Americans and Europeans, the original

natives were quickly driven out, replaced by American trapping parties and gold

prospectors in the 19th century. By 1850, the United States Army had

annexed the southwest regions of the Mojave, and transportation routes began to

zigzag across the barren landscape. Native Indians such as the Mohaves and the

Chemehuevi got displaced onto Indian Reservations, and mining towns began

popping up all over the desert. Of course, the mining boom quickly died out as

settlers moved on from the unforgiving desert conditions; rainfall and

vegetation began to decrease during the 1860s, and ranchers and miners

abandoned the area accordingly. 1912 saw a series of years of good rainfall,

but this bout of moisture dried out soon enough, discouraging pioneer settlers

and forcing them to move on. Many ghost towns and lone farmhouses from this

period still stand in the Mojave today (Webb 60). Over the late 20th

century, a gradual increase in temperature and dry conditions have been noted

(Webb 23). Perhaps because of the instability of the global climate, throughout

the 1970s and 80s, episodes of long drought seasons have fluctuated with wet

periods.

Today, the average annual rainfall ranges from 0 to 250 mm

(Webb 171). 64% of the rainfall occurs during the winter, producing a balanced summer-winter

rainfall ratio (Webb 4). El Nino cycles bring in heavier rainfall, which have

become more frequent in the last 20 years (blueplanetbiomes.org). Most

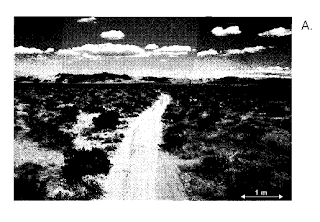

plants are perennial, and the entire Mojave desert is characterized as desert

scrub, and includes plant types such as “the creosote bush scrub, saltbush scrub,

shadescale scrub, blackbush scrub, and Joshua tree woodland” (Lovich and

Bainbridge). These vegetations do not grow in profusion, and are scattered

across the Mojave topography that alternates between mountains and basins. Salt

flats where sand and gravel have drained contain borax, potash, salt, silver,

tungsten, gold, and iron that can be extracted. The Mojave is classified as a

“high desert” that serves as a transitional area between the Great Basin Desert

(north of the Mojave) and the Sonoran Desert that shares Mojave’s southern

border. Elevations of the Mojave range from 2,000 to 6,000 feet (Somerville).

Animals in the desert include herbivores such as the kangaroo rat, which

forages for seeds in the desert sand, as well as carnivores such as the great

horned owl, coyote, bobcat, and snake. Birds and lizards also form communities

near the perennial plants, making nests or dens while feeding off small rodents

or termites or stinkbugs that feed off dead Joshua trees (digital-desert.com).

Works Cited:

Webb, Robert H., Lynn F. Fenstermaker, Jill S. Heaton, Debra

L. Hughson, Eric V. Mcdonald, and David M. Millar, eds. The Mojave Desert: Ecosystem Processes and Sustainability. Reno,

Nevada: University of Nevada Press, 2009. Print.

.PNG)

_key.PNG)